| Selected Articles: |

| David Jager Sook Jin Jo: Sacred Space, Reclaimed Material WhitHot December 2024 |

| Jonathan Goodman Out of the Ordinary: A Conversation with Sook Jin Jo Sculpture July/August 2021 |

| Jonathan GoodmanSook Jin Jo Sculpture November 2018 |

| Margaret Richardson Sook Jin Jo: Seeing Beyond the Clouds 2016 |

| Jonathan Goodman Sook Jin Jo: Approaching the Mystery of Things Fronterad 2016 |

| Sara M. Picard Sook Jin Jo: Transformations 2015 |

| Margaret Richardson Walter Gropius Master Artist Series Presents: Sook Jin Jo SouthEastern College Art Conference 2012 |

| Jonathan Goodman Sook Jin Jo: The Limits of Art, the Limits of Life ß 2011 |

| Barbara MacAdam Sook Jin Jo Art News April 2010 |

| Simon Baur Sook Jin Jo, In Between Kunstbulletin September 2010 |

| Robert C. Morgan Sook Jin Jo World Sculpture News Hong Kong, Volume 16 Number, Winter 2010, p.74 |

| Yu Jae-Kil Meditative Space for Others Space October 2007 |

| Richard Vine Amazing Grace: The Works of Sook Jin Jo 2006 |

| James Kalm Sook Jin Jo Brooklyn Rail, February 2006 |

| Todd Siler Sook Jin Jo’s Journey to the Heart of the Human Spirit 2006 |

| Eleanor Heartney Sook Jin Jo Art in America April 2005 |

| Donald Kuspit The Power of Meditation: Sook Jin Jo’s Art 2004 |

| Kate Bonansinga The Evolution of Wishing Worlds: An Interview with Sook Jin Jo 2004 |

| Robert C. Morgan The Spokes of the Wheel Sculpure September 2003 |

| Yongdo Jeong Beyond Being and Non-Being Art in Culture September 2002 |

| Mary Schneider Enriquez Sook Jin Jo Art News June 2001 |

| Robert C. Morgan Sook Jin Jo 2001 | Jonathan Goodman Sook Jin Jo Sculpture June 2001 |

| Donald Kuspit Sook Jin Jo by Donald Kuspit 1996 |

| Amy Fine Collins and Bradley Collins Sook Jin Jo Art in America June 1990 |

On the Cover: Sook Jin Jo, "Cathedral: Korean Ex-Votos," 2002.

The Spokes of the Wheel: Sook Jin Jo by Robert C. Morgan

My interest in the Tao Te Ching—the great text said to have been spoken by the legendary Chinese sage Lao-tzu in the 6th century B.C.E.—began many years ago while I was living in Santa Barbara, California. I recall those blissful days, sitting and reading on the cliffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean. When I got tired of reading, I would walk for miles along the beach, collecting shells, stones, and pieces of driftwood swept by the force of the waves into the sand. In such an environment my mind moved easily toward thoughts of Eastern spirituality. After spending time each day at the seashore, I would return to my small apartment, make green tea, and contemplate a verse from the Tao Te Ching: “We join spokes together in a wheel/ but it is the center hole/that makes the wagon move.”1 Many years later, after settling in New York City, I returned to this passage one day during a conversation with the Korean sculptor Sook Jin Jo. I had long admired her constructions made of found wood and was eager to learn about the aesthetic ideas behind the work. In viewing Jo’s assemblages, I find it difficult not to consider the words of Lao-tzu. In a work titled Space Between (1998–99), she has added a subtitle that quotes directly from the concluding stanza of the passage cited above: “We work with being, but non-being is what we use.”

To see the actual sculpture to which this passage refers is to understand the meaning. Jo has constructed a kind of pyre, an open structure in which branches have been cut and assembled into square units rising from the ground to a height of 10 feet. The opening inside the branches is a spatial enclosure, implying a kind of sacred space, a static hollow entity or a celestial well where spirits of heaven and earth reside. Through the horizontal placement of the branches one can see the light, thus revealing the interior from all sides. One can read the meaning of the enclosure as containing the spirit of the senses. As with many of Jo’s constructions, there is an active engagement with the work as a shelter that nurtures body and soul. One could say that the Tao in Space Between is built on the absence of worldly things. Without them, this empty container functions as a kind of poetry. The Windows of Heaven are Open (1995), composed of a horizontal line of old and empty window frames abutted against one another, with two broken folding chairs placed on the floor to the right, holds a pregnant emptiness—what in Zen Buddhism is called by the Sanskrit term sunyata. Here, the self is allowed to vanish, to escape the drudgery of formal analysis, the redundant theories of identity politics, and the agonizing rhetoric of otherness and subjectivity.

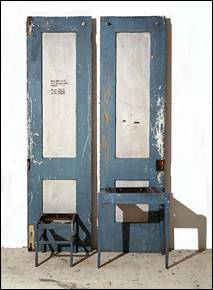

A similar concept is embodied in the related work We are standing in His presence (1998). There is a trace of cerulean paint, faded and scraped, on two upright door panels. In front of each panel is a table frame, the right one larger than the left, that keeps the viewers at a distance. The sheer beauty and exaltation of found simplicity, as in Shaker furniture, is visual and practical. We are standing in His presence offers a statement of simple beauty that connects with the structural and physical elements. The form abides within itself. It transforms presence into absence and thus engages the viewer in a transcendent phenomenon. The concept of absence in Taoism functions less as a theory than as an affinity. More than a guide, it offers an inspired way of thinking and feeling, a way of discovering the language of art. This ancient though modest transcript holds a fascinating breadth of knowledge. Many of the intuitions employed in Jo’s constructions are indirectly noted in the Tao Te Ching. For example, there is the notion of oppositions held in suspension, the interplay and overlay between one force and another, the subtle reversals of power, the course of nature as a way of understanding the present in relation to the past and future—these are ideas related phenomenologically to the way one may approach an experience. Jo works with wooden forms in the context of an installation or an environment. While the parts make up the whole, the whole is always greater than the sum of its parts. I am attracted to the deliberate lack of precision in her work, the way things come together in a crude, unfinished way. This concept of the unfinished in her magnificent wooden constructions is intentional. As she has explained in a written statement, her work intends to express “the essence of materials” as belonging to “the order of the cosmos: the ultimate revelation of why things exist.”2

This is another way of saying that being and non-being are inseparable. But the focus on non-being is what allows being to emerge. This comes close to the spirit of Zen, a philosophy with a strong historical and philosophical affinity to the thoughts of Lao-tzu. In the West, the author Alan Watts has been particularly important in clarifying the relationship of Zen to the creative arts: “Although profoundly ‘inconsequential,’ the Zen experience has consequences in the sense that it may be applied in any direction, to the conceivable human activity, and that wherever it is so applied it lends an unmistakable quality to the work.”3 The spirit of Zen is applicable not only to the way we think about Jo’s sculpture, but also to the process by which her sculpture is made. The process evolves through the application of found objects—things from the everyday world, eroded objects that have washed up on the beach or have been deposited in a junkyard, subjected to rain, wind, heat, and snow. As our post-industrial world becomes infested with worn-out machinery and discarded gadgets piling up in our global dumping grounds, Jo has discovered in these “waste products” numerous possibilities for sculpture. Cathedral: Korean

Ex-Votos (2002) was constructed from 500 wooden objects suspended

in a highly congested arrangement from the ceiling of a corridor-like

gallery space. The impact of this impressive installation implied a

kind of excessive fusion between Jo’s indigenous Korean culture and

what she acculturated from her Brazilian experience a year earlier in

Itaparica (Bahia). During the two-month residency in

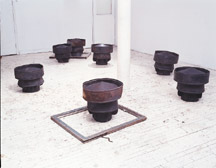

On a visit to Brooklyn three years earlier, she discovered

several discarded solar turbines, made of steel, all rusted and bent.

She had them delivered to her studio in Chelsea, where she placed them in an indeterminate

visual field directly on the floor. Jo became interested in the space

between the rusted turbines, how they commanded the space and, in a

certain way, defined it. She decided to place an old window frame around

one of the turbines, thus setting off a singular space in relation to

the whole. This Zen Garden (1998) refers to the famous gardens

in Kyoto, such as the Ryoanji,

and to the isolated mountain temples north of Gwangju

in In keeping with her sculptural aesthetic, Jo was commissioned to build Meditation Space (2000), a work using tree trucks, branches, and old floorboards from a former Zen Center in upstate New York. It was conceived in such a way that the structure becomes virtually transparent by optically disappearing into its forested surroundings. Meditation Space appears nearly as a mirage, a specter, a dissemblance of material reality within the scope of nature’s force and intrinsic power—a parallel statement to the force of the Tao itself—a compelling work of art that reclaims peace and reconciliation in a chaotic and desperate world.

In a work such as Meditation Space that coincides with its environmental habitat so completely—as, on a grander scale, Frank Lloyd’s Wright’s Falling Water does in Bear Run, Pennsylvania—the consciousness of non-being comes alive and is transformed into consciousness. Here the wheel of harmony and the unity of oppositions begin to turn. In the forest, amid the growth of plant and animal life, and its concomitant decay, the inner-spirit of Jo’s work may be felt. This kind of overlay between physicality and dematerialization is precisely what the art of Sook Jin Jo is hoping to achieve—an essence of objecthood that exists concurrently between two worlds, the material and its unknown spiritual counterpart. Robert C. Morgan’s recent books include The End of the Art World (1998) and Bruce Nauman (2002). Notes: 1. Lao-tzu, Tao Te Ching. Translated by Stephen Mitchell. (New York: Harper Collins, 1988), Verse 11. 2. Sook Jin Jo, untitled statement, 2002. 3. Alan W. Watts, The Way of Zen. (New York: Pantheon Books, 1957), p. 146.

Sook Jin Jo: The Limits of Art, the Limits of Life by Jonathan Goodman

As one of Korea’s most interesting artists, Sook Jin Jo has fashioned a career that offers people many different kinds of art: sculpture, drawing, performance, installation, and public works. Intent on working at the interstices of categories, where sculptures subtly merge with installations, or drawings document performances, Jo has shown us it is still possible to find creative niches that feel both traditional and contemporary. Jo’s sculptures, perhaps the most prominent of her media, depend upon found materials—usually wood or furniture taken from the streets early in the day, before being picked up by refuse collectors. Her dependence on the random appearance of appropriate materials gives her art a magical feeling; it is as if the lives of those who lived previously with the wood had somehow become present in the resonance of the objects found by the artist. Jo, whose art is characterized by presence and absence at the same time, employs used materials because their scarred surfaces suggest life before their use as art. But it Is also true that she is suggesting a world beyond that which we inhabit—a world that inevitably reminds us of our own death. By combining presence and absence, Jo clearly seeks the expression not of religious dogma so much as the spiritual awareness of the life events responsible for such doctrines. It happens, then, that the spiritual life Jo posits—seen, for example, in COLOR OF LIFE, a 1999 performance at Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, where participants in open, stacked barrels considered their own death—involves the close study of mortality. Yet Jo, who is sharply cognizant of the limits of her life and those of others, documents her recognitions as filled with a belief that may best be described as holy. The unconventional nature of her attitude, what we might call a concerted meeting with death, results in insights that take on a deep seriousness without becoming somber or morbid. This is, given Jo’s choice of subject, exceedingly hard to do, and one of the genuine pleasures of her art is seeing her work as catholic and ecumenical—in other words, free of rigid doctrine—in the face of death’s awareness. Some of Jo’s most successful pieces have to do with meditation spaces in the woods, where someone can contemplate basic ideas and feeling within the solace of nature. In one instance, a meditation space built in the year 2000 in upstate New York, her arrangement of four open walls of branches do not protect the participant from the vicissitudes of the weather; instead, it suggests that nature can offset but not do away with the primal questions of our existence. In Jo’s setting, meaningfulness derives from our contemplation of such questions, even as we know that we cannot transform the limitations of life. Jo’s emotional depth, faced with the psychic complications of impermanence, infuses all of her art with a seriousness of purpose. This does not mean that she is hopelessly grim and lacks humor; indeed, one of the pleasures of knowing her is that she possesses a humorous candor that lightens her essentially earnest nature. For me, Jo is a sculptor first and foremost, and we must remember that sculpture’s original function was to furnish a memorial for the dead. All the remarkable developments in this field cannot take away sculpture’s primary purpose, the memento mori. In a magical way, Jo seeks to translate the particulars of memory into a profound, worldwide understanding of its space as a center for the healing of loss. She knows that loss is central to everyone’s experience of life, but she also proposes that art can both sanction and ameliorate its experience in terms that reflect a positive, indeed a nearly sanctified transformation of mind. She sees the Big Picture, then, but she does not allow it to dominate her lively, finely honed imagination. Part of her truth stems, as we have seen above, from her inspired use of materials, but there is also the presence of the spirit animating these materials in spiritual ways. How else does the spiritual manifest itself in Jo’s work? Well, for one, she has worked with poor school children in Bahia, Brazil, close to a studio where she had a residency fellowship to make art. Jo and the students decorated an outside wall of the school together, in a common effort that expressed itself as much as a performance as the group’s production of art. This small project became a statement of pride and ignited the children’s interest in art; such communal activities reflect Jo’s concern with the world beyond the sometimes close confines of the art scene, where posturing and vanity can get in the way of making good work. Indeed, on a profound level, the project shows us the depth of Jo’s commitment to an esthetic that relies on shared materials and effort, which lend an ambient energy to the combined work and its realization. Her point is not only to create, but also to help young people understand the potential of their own creativity, which animates absence or emptiness. Something is done to work out a strategy ennobling our limited lives, whose purpose remains beyond our comprehension. Art can lend dignity to anyone’s circumstances, no matter how straitened they may be. We can see Jo’s determination in a public work completed in 2009, entitled WISHING BELLS: TO PROTECT & TO SERVE, done in an outside site in Los Angeles, next to the newly built detention center for the Los Angeles police. Here, Jo, who despite her Korean background has been careful to address her audience in non-Asian terms, uses a Buddhist approach to her project. For the outdoor installation, cedar columns were introduced as supports for a metal matrix from which 108 bronze bells are hung; the number of bells corresponds to the number of desires recognized in Buddhist thought. Hanging from each bell’s clapper is a positive tag, marked with words such as “Kindness” and meant to offer hope to those who pass through the installation. For Jo, the point of the project has been to extend solace in situations where it is badly needed. The native decency of Jo’s sensibility may be read as part of her creativity in general, in which a sense of conviction is mirrored by an original intention. In fact, Jo is uncommon in that her intentions become as important as her expressiveness. But then this is part of her general directness of purpose. Walter Gropius Master Artist Series Presents: Sook Jin Jo

Formerly a railroad hub on the Ohio River, Huntington is a community in transition, working to repurpose abandoned buildings and breathe new life into a depressed region. Its focus on reconstruction and renewal made it an ideal setting for the work of Korean-born artist Sook Jin Jo. Based in New York since 1988, Jo creates sculptural assemblages, installations, and public works that explore the significance of discarded materials collected from natural and urban environments. Her work offers a new perspective on abandoned objects and sites. In Spring 2011, Jo was invited to participate in the “Walter Gropius Master Artist Series” at the Huntington Museum of Art for which she delivered a public lecture, led a workshop, and exhibited three assemblages and a site specific installation entitled OUTSIDE IN. Videos documenting OUTSIDE IN and a previous work, entitled CROSSROADS (2008), were included in the exhibition, revealing the collaborative and ephemeral nature of Jo’s works. Coinciding with the release of a catalogue of her work and featured on its cover, this exhibition provided a glimpse into the themes that define Jo’s career.1 A physical and semantic inversion, OUTSIDE IN is a play on words and space which locates viewers in between outer and inner states. Installed in two separate spaces of the museum, it provokes viewers to make connections and meditate on the theme of transformation. Half of the work is encountered from inside the museum’s main corridor which is lined on one side with windows and doors that open into the courtyard outside. Looking or moving outside, one finds a gnarled mass of wooden pieces set against the solid exterior brick wall of the adjoining gallery that seems to grow through the wall into the building. Curiosity propels viewers back inside where the other entangled half, lurching into the gallery’s space, seems to come through or push back against the wall. Working with local volunteers, Jo spent over two weeks gathering and installing these twisted tree branches, pieces of furniture, and other building and industrial fragments collected from the museum’s grounds and an abandoned house along the Ohio River.2 Like a hunk of driftwood collecting debris as it floats downstream, natural and manufactured pieces of wood are interwoven, nailed and propped against themselves and the wall as if together providing new support and reaching both outside and in. Debris morphs into sculpture and into architecture, dissolving the boundaries between these categories.3 As viewers are led out and in, the materials themselves tell of similar journeys. Outside rubbish is brought into the museum, transforming its status as refuse. Reoriented and commingled, these materials suggest a history of use and place; worn surfaces reflect destitution and decline as well as endurance and regeneration. The interplay of out and in, space and mass, natural and manmade, stasis and growth connects Jo’s tangled thicket to the other works on display. On the opposite wall, for instance, STREETS OF INDIA (2009) dominates, providing a contrasting sense of order to the tumbling chaos of OUTSIDE IN. As the title suggests, this work also recalls a place. However, while organic disorder dominates OUTSIDE IN, here, human intervention prevails. It is as if the cluttered streets and grit of New Delhi have been collected and contained within.4 Random boards of wood are arranged vertically, matched, fitted, and nailed together, overlapping and projecting from the wall. Varied surfaces—painted, stained, raw, smooth, carved, and punctured—complement the materials in Jo’s installation. Although the original function of the fragments is at first unfamiliar, closer inspection reveals bits of gray-blue beadboard and shiny gameboard, alongside frames, metal springs, and what appear to be drawer fronts and other furniture parts with dowels still protruding. In this respect, both works stimulate the imagination as the viewer’s eye searches for familiar forms among the fragments, which requires one to seek new meanings and interpretations. This effect is even more obvious in CHAIRS(2010). Collected in New York City, various chair seats fan out from the corner of the gallery. Legless, they sit directly on the floor, their backs erect and expectant, as if waiting new purpose. Intertwining presence and absence, there is something poignant about them, for chairs, like wood, can evoke the human form and its outer skin. Fitted for the body, one can imagine sitting in them as they simultaneously appear to be sitting or kneeling themselves, their varied surfaces and shapes—curved or straight, scratched, pocked, or smooth—recording a lifespan. This phenomenological experience of objects in space paired with emphasis on association, placement, and the intrinsic spirit of materials recall Assemblage, Arte Povera, Minimalism and Conceptualism as well as themes of Buddhism and Taoism. Jo manages to fuse these references seamlessly as she fits together irregular pieces of wood and connects them to life. Just as nature, communities, and humanity go through cycles of growth, decay, and rebirth, materials once activated by use and then discarded find new life here as art. Jo brings these objects from the outside world together inside, drawing attention to their metaphoric potential and inner spirit. With them, she creates new spaces to explore, inviting us to move out, in, and between the materials. Like the feature installation, Jo’s works compel us to connect opposites and think in reverse. As we contemplate what is absent from what is present, that which was abandoned is found again. Humanity’s spirit can be discovered in its refuse, as we can see renewal in ruin. We begin to look at the remnants around us from the outside, in.

Margaret Richardson,

Independent Scholar Notes: 1. "Sook Jin Jo: Complete Works 1985-2011", with essays by Jonathan Goodman, Donald Kuspit, Todd Siler, Robert C. Morgan, and Simon Bauer (Gyeonggi-do, Korea: Maronie Books, 2011). Notes: 2. Museum brochure, Sook Jin Jo: Walter Gropius Master Artist Series (Huntington, WV: Huntington Museum of Art, 2011). Notes: 3. In her lecture, Jo mentioned her interest in “breaking boundaries between painting and sculpture and form and space.” Sook Jin Jo, “Walter Gropius Master Artist Series", (lecture, Huntington Museum of Art, Huntington, WV, April 14, 2011). She also provided the following description: “Outside In will be an exploration of connecting the space between the inside Switzer Gallery and the outside courtyard space beyond the wall in between by intertwining wood scraps, branches, and industrial refuse in random shapes and positions. During the process, we will also explore the relationship between art and architecture, construction and deconstruction, nature and man-made, structural stability and mystical energy. "Walter Gropius Master Artist Series Presents: Sook Jin Jo", Huntington Museum of Art, http://www.hmoa.org/exhibitions/past. Amazing Grace: The Works of Sook Jin Jo

Over

the past 20 years, Korean-born New York-based artist Sook Jin Jo

has produced drawings, collages, sculptural assemblages, and installations

that reveal two abiding, interconnected thematic concerns. Formally,

her works combine a strong, almost minimalist, sense of pure structure

with an intensely sensual – even empathic – love of rough-hewn materials. Conceptually, they

invite a meditative (and sometimes physical) interaction with asymmetrical

balances and unexpected harmonies of color, texture and shape – all meant to induce a state of well-being in

the viewer. Form, meaning, and effect are thus united by a single

spiritual purpose: reclamation.

People who meet the artist are often startled by the contrast between

her refined, modest person and the brute elements of her practice.

At the beginning of her career, when she could not afford expensive

art materials, the elegant young woman began scouring the city streets

looking for discarded objects that she could haul back to her studio

and incorporate into her work. Although she professed a desire to

create peaceful, engaging artistic environments, her choices were

surprisingly crude: broken and discarded furniture, old window frames,

weathered planks, worn-out shoes, gnarled branches, etc. Her goal

could sound idealistic when put into words: “Since I was a child

I had a dream to create beautiful works and environments that inspire

people’s creativity, uplift the spirit and heart, and that many

people can interact with.” But her visual and psychological instinct

drew her to materials that acknowledge the harder experiences of

life – sickness,

abandonment, aging, neglect – the everyday traumas that make redemption (whether

artistic or spiritual) so deeply needed, and so powerful when it

comes.

Indeed, many of Jo’s best sculptural pieces, though never forbidding,

are relatively austere. The Windows of Heaven Are Open (1995)

consists mostly of emptiness, defined by five abutted window frames

and two damaged chairs. The wall piece Resurrection II (1996-97)

features 46 wooden drawers of various types and sizes, each containing

nothing.

Such works imply that the artist, like any seeker in the Buddhist

and Taoist traditions of her childhood, had to go to the depth of

solitude before beginning to reach out – in an ever more socially

active manner – toward other isolate souls. Meditation Space (2000) signals a transition. Based on an earlier studio work, Space Between/ We Work with Being, but Non-Being Is What We Use (1998-99), the tall latticework wood structure has public elements

added – a doorway and bench – and stands in a woodland where it can provide

rest to hikers. Chronologically, it follows Jo’s first major public

project, Color of Life (1999), a grid of stacked metal barrels

that drew myriad participants, young and old, to clamber on the

work’s frame and lie contemplatively in the brightly colored tubes.

Since then, Jo has collaborated with schoolchildren and local residents

in

Although one can find formal affinities in Jo’s work to that of

Eva Hesse, Barry Le Va, Jannis Kounellis and others, she

has always created in an extremely personal fashion. Of late, she

has made several site-specific variations of an installation that

memorializes her brother, who died recently at a tragically young

age. The labyrinth of scrap lumber and twigs, where viewers wander, repeatedly finding new routes and new perspectives, reminds one that

the lamb lost in the wilderness is a principal metaphor in Jo’s

adopted Christianity. It is no surprise, given her longstanding

use of salvaged materials, that this artist would be drawn to a

strongly redemptive faith – one which holds that the lost

can be found, the sinful saved, the physical transcended. In 1998,

Jo made We Are Standing in His Presence, a work composed

of two table frames and two battered doors, on one of which she

scrawled: “None else could/ heal all over soul’s/ diseases . . .

/ We are standing/ in His presence/ on holy ground.” In that humble

sentiment lies the highest aim of her art.

Stepping into the sculpture yard behind the gallery, I was enveloped

in another world far removed from metropolitan domesticity. On my

initial visit, there was a light layer of icy snow caked on parts

of Sook Jin Jo’s wooden installation. It provided a frosty crunch

as I walked around and through this rambling gnarled construction.

The sun was setting, but the natural light played on the white of

the snow and brought the various forms into strong contrast, creating

a sense of primitive wilderness like stumbling into an isolated

glen on a high, wind-swept plateau. The sculpture space at Black

and White is a rectangle of quietude, with blank walls that rise

up at least four meters, a unique site, and perfect for the presentation

of Jo’s My Brother’s Keeper.

Taken individually, the elements have a strong connotation of collage.

Upright members are twisted and kinked in apparently organic shapes.

Up close viewing reveals that the limbs and posts are cut and joined

from an ironic amalgam of raw wood and milled and lathed lumber.

Weathered branches have scraps of boards and worn architectural

remnants inserted into their configurations as if a pre-industrial

forest had collided with and embraced a post-industrial one. Jo’s

eye for analogous forms presents us with a salient insight into

a material often taken for granted: wood. The structure’s coherence

is reinforced by its spectrum of earthen and woody browns, accentuated

sparingly with only a few sticks of faded enamel color. A shape

that might be the trunk of a sapling is propped up by what should

be a ragged root, but the spiral end of an oak banister is substituted.

A cylindrical limb has a two-by-four grafted in its middle, pricking

the awareness of just how much of our constructed world is cut out

of the stuff of nature. Vertical posts or shoots are braced upright

by a ramshackle network of crossbeams and buttresses. While moving

around and among the different components of My Brother’s Keeper, readings at different

points change from architecture at its most primitive to a blighted

forest with leaves and greenery desiccated to a climb over a junk

pile of discarded lumber headed to a bonfire. There is, underlying all the formalistic and “artistic” structural

intentions of this work, one uniting theme that Jo’s selection of

wood is sublimely and poetically appropriate for: the inevitability

of death and decay. One becomes instantly aware through sight and

smell of the fragility of even the most sturdy log or beam to the

forces of time, wind, weather, and rot. Sook Jin Jo’s My Brother’s

Keeper delivers to us the same insights into nature

and our place within it that we might experience during a winter

hike through distant forests. SOOK JIN JO’S JOURNEY TO THE HEART OF THE HUMAN SPIRIT

When I first encountered Sook Jin Jo’s site-specific installation, “All Things Work Together” (2004), at O.K. Harris Gallery in New York City, I felt I had wandered into a forest vacant of wildlife other than human imagination. Gnarly branches of actual trees animated the space in a stimulating way, without evoking dread or those daunting feelings of loss and loneliness. Standing in the thick of this sculpture’s restless mass of raw energy, I was instantly absorbed by awe and wonder. Jo’s work quelled my fears by raising some uplifting thoughts: perhaps, our world isn’t hopelessly lost in the anarchy of the universe and its violent wilderness. Maybe we’re missing something that’s bigger than life—something only the art of higher consciousness can help us see and grasp! Otherwise, “what’s the point of the universe?” as one 12-year-old recently asked me in perfect innocence.

How do all things work together? I thought. How do networks of human beings, for instance—who metaphorically resemble these riley, irregular-shapes, unpredictable tree parts in Jo’s art—work as one integrated system? Are the symbols and messages nested in this sculpture pointing out some ways in which all things are connected? Or is the artist simply imbuing her work with a litany of unspoken questions about nature’s grand connectivity, leaving us in the dark with our personal responses and little more?

The sculpture beckoned me to venture deeper into its virtual wilderness. As I started searching for Jo’s points of insight—musing about its larger purpose and potential—suddenly, a paradox filled my field of view, testing my fuzzy logic about life. I realized things don’t have to make sense to be meaningful. Things don’t have to be directly connected to be connected—or to connect with you in profoundly physical ways.

There’s a bridge of aesthetics that connects Jo’s work to the artistic sensibilities of sculptor Jannis Kounellis, the Greek Arte Povera Artist, who aimed to lift art to new heights of reality with his constructions of found weathered elements in the 1960s. Kounellis also introduced live horses in his art installations for more than sensational dramatic effects; in fact, it infused the symbolisms we use to represent reality with “the real thing.” It interrelated the power of one with the other. Symbolism and reality were no longer thought of as parallel playing, so to speak. Instead, Kounellis recognized them as one-and-the-same thing: aspects of life.

The Conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth dared to do something similar in 1965 when he presented his bold artwork, “One and Three Chairs.” Kosuth’s concise installation consisted of a photograph of a chair, a physical chair, and a common definition of chair. This artwork drew attention to the reality of our symbolic world, welcoming our deeper experience of it.

However, absent from these two artists’ intellectually composed, conceptually oriented work is that elusive thing [the soul], which we still can’t quite describe. And yet, we seem to know it the moment we experience it. You can see the soul in Sook Jin Jo’s minimal installation, “The Windows of Heaven Are Open.” It’s seated in the two folding chairs that stand before five open window frames without glass or screens to filter the world. It can be seen just beyond these wooden frames, in plane view, where one’s eyes tend to gaze at the future.

Sook Jin Jo’s artworks make evident how all symbolic things, whether born from art or life, possess a tangible life force that Eastern cultures broadly call spirit and Western cultures narrowly label energy. This spiritual energy exudes its presence in many of Jo’s works, such as Tombstone Landscape/Being is Born of Non-Being with its expansive array of weathered, broken, antique skis and battered wooden boards. If you take the time to dig into the Tombstone Landscape, you’re likely to spot some of the same influences that energized Kounellis’ sculptural assemblages; namely, the uninhibited expressive marks we see in the works of Jackson Pollock and even in Robert Rauschenberg's “Combine Paintings." Although the individual styles of these artists are not strikingly obvious in Tombstone Landscape, nevertheless, you’ll feel the unique connection their creative energies have with Sook Jin Jo’s constructions. It’s not that they all have something in common materially that counts. It’s that they all share spiritually something that can never be counted.

Allowing my curiosity to journey farther, I discovered in Jo’s artworks elements of joy that come from real collaborative learning experiences propelled by bold purposes and urgent initiatives. *

It’s no stretch of fiction to link Jo’s objects and artistic objectives with the adventurous work of the pioneer environmental artist, Gyorgy Kepes, founder of M.I.T.’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies and author of the influential book series Education of Vision. Whereas Kepes’ work turns our vision of the world outside in—treating us to see the “new landscape” as rendered by technological innovation—Jo turns our world vision inside out, inviting us to experience what can only be seen and known by imagination alone.

“In the beginning is my end,” wrote TS Eliot in 'East Coker,' Four Quartets. Sook Jin Jo’s Tombstone Landscape appears to visually echo this timeless wisdom extending Eliot’s message “to be still and still moving.” Whether Jo’s sculptural muse pulls you into the gravity of its presence, or pushes you upwards with its existential thoughts on being, it quietly engages us to begin to see the whole of art as life without an end in sight.

Sook Jin Jo

Sook Jin Jo has a way with wood: she takes tired, old, abandoned pieces of it, often fragments of demolished buildings—old doors and shutters, and plywood panels—and assembles them in eloquent constructions, full of melancholy serenity. A fragment is emotionally uncanny, and Jo uses her fragments to great emotional effect. She is extraordinarily sensitive to irregularity: the grain in wood, the erratic shapes of fragments. In her hands, they become a kind of gestural nuance, full of unexpected grace and poignancy—a felicitous found “automatism.” At the same time, Jo's constructions are ingeniously self-contained and regular—geometrically clear. Overall, they are carefully balanced harmonies. Inwardly asymmetrical, outwardly symmetrical, they show the occult in action. She has made, out of fragments, symbols of incompleteness and ruin, works of art that are complete and whole and absolute. She uses her primitive materials with great refinement. Art is a way of reclamation and renewal for Jo, even of redemptive transformation: she shows there is still esthetic life in dead things. She does not deny disintegration, but shows that it can lead, unexpectedly, to a new integrity. Her work is not “junk sculpture” in the ordinary sense. She is not just accumulating detritus to ironic effect, as though to mock society with its own waste. Rather, she is a formalist, using “deviant” materials. The play—simultaneity—of two and three dimensions in her pieces counts for more than the particularity of any material. The tension between line and painterly surface—axiomatic geometry and spontaneous gesture—matters more than the fact that her materials were found in the street. She is a modernist, overcoming ordinary esthetic differences, and always true to her medium, apart from its social meaning. She is “street smart,” but, more than that, art smart. Thus the various There is nothing arbitrary and vulgar about Jo's abstract compositions, as there is about the crude materials found on the street. André Breton once said that the dialectic of street and museum haunts modernist art: the point is to look at the street with a museum eye, that is, to see its transient things from the viewpoint of eternity—to see the potential eternity in them. While an artist like Alan Kaprow chose to emphasize the street at the expense of the museum—for him Forty Second Street was more vital than any museum—Jo strikes a judicious balance between them, recognizing that the museum is not so much a mausoleum and morgue, as Kaprow thought, but a symbol of transcendence. And to achieve transcendence is to heal a wound: the fragments she finds in the streets are like injured birds, who are given new artistic wings in her works. For Jo, art is not just a faded repetition of life—in her case an echo of materials that are themselves echoes of life—but an esthetic transformation of it that points to a meaning beyond yet latent in it, and that makes it more meaningful than it ordinarily seems to be. Jo’s works are thus both memento mori of the street and symbols of a higher consciousness that transcends it. T. W. Adorno has argued that in modernity art oscillates between the poles of Constructivism and Expressionism, and that each is at its best when it has nothing to do with its opposite. But part of the point of postmodernity is that such purity has become empty; only the fusion of the traditional modernist opposites—a subtle, synergistic hybridism—can create a sense of esthetic resonance, that is, rich affect and symbolic pregnance, as Clement Greenberg called it. This is what Jo gives us: expressionistic constructions. Even more, she has used her wooden fragments to construct a kind of expressionistic still life. This seems especially true of her paper works; each part seems autonomous, and has its own flair and intensity. But the synergism between them is truly expressionistic: they seem about to erupt beyond their borders, even as the work as a whole remains stable. The paper works, as well as the ongoing series entitled At the same time, her works have an inherent, brooding grandeur, enhanced no doubt by their tableau format, that invites meditation and self-communion. Indeed, the monumental horizontal works, such as |